By David Abel | Globe Staff | 7/13/2003

ISTANBUL -- Naked, alone, and sweating after another sleepless night, I gaze at the shafts of light shooting through holes in the 500-year-old dome, waiting fretfully for the stocky man whose calloused hands will soon grind the tension from all my aching limbs. Lying on a large block of soapy marble, which feels like a sacrificial altar as steam rises all around, I fall into a groggy state where dreams blur with reality and the past slowly consumes the present.

As if experiencing them all over again, my mind flashes images of lava-sculpted canyons, turquoise lagoons, and relics of civilizations dating well before Christ. I smell the toasted pita breads, roasting shwarma, and the sacks of spices flaunted in the markets. I hear the high-pitched call to prayer ringing from the minarets, I taste the rush of honey oozing from a chunk of baklava, and I feel the warmth of the Mediterranean banish Boston to a distant memory.

These are the last hours of a whirlwind, 10-day tour of Turkey. Back in Istanbul after a long night on a crowded bus from the southern coast, a trip that briefly stranded me on the Asian side of the city, I'm in a bathhouse built before Columbus discovered America.

It's early on a Sunday morning, and with tourism still suffering from the war in Iraq, I have this vast place to myself, and the movie playing in my mind.

It starts with a mix of holiness and haggling, mediated by small glasses of apple tea and belly dancing. The trip from Istanbul's massive millennium-old mosques to the Grand Bazaar may be short, but it takes a while to go from the grandeur of the Aya Sofya, a sprawling Roman Empire-era church converted into a mosque, to the maze of merchants peddling everything from pricey carpets to cheap pottery.

The contradictions are everywhere - and they are what make this continent-straddling city, and country, so alluring. The melange of Europe and Asia, or secular West and sacred Middle East, is visible in the McDonald's next to a mosque. Young women shrouded in headscarves shopping in music stores playing Eminem. Nearly pornographic movie posters beneath the ubiquitous minarets.

In this land of extremes, contradictions arise even in the most rudimentary communication. Of the few Turkish words I learn, the indispensable ones are cok guzel, "very beautiful or very nice," and sao ol, which literally means "stay alive" but translates into something between "no thanks" and "leave me alone."

As the film rolls in my brain, I'm on a ferry plying the Bosporus, both awed by its shimmering beauty and aghast at 3,000 years of blood spilled for control of this strategic waterway, which separates Europe and Asia by connecting the Mediterranean with the Black Sea. On the European side, I see the mosques and palaces of the Ottoman Empire towering over a jumble of ugly modern buildings. On the shores of Asian Istanbul, where fewer tourists venture, there is a similar cacophony, though with less grandeur and more fishing boats.

The image fades, it's now dark out, and I'm on a large bus, something like a gussied-up Greyhound with Turkish carpets on the floor and a stewardess serving a round-the-clock assortment of tea, fruitcakes, and a special lemon-scented cologne. The road is smooth as we barrel through the night into the nation's heartland. But sleeping proves difficult, especially with the hourly stops.

Speed is not a priority. With bus stations here like convenience stores in America - everywhere, always open, and always bustling - there is a good excuse for not rushing. Around 3 a.m., somewhere in the salt flats between Istanbul and Cappadocia, I open my crusty eyes to find a party. The early-morning revelers - scores of families, lovers, and solo travelers - are yapping over tea or raki, the smooth Turkish liquor. There are old men cooking kebabs and young children trying to sell me a visit to the bathroom, which they maintain for a fee.

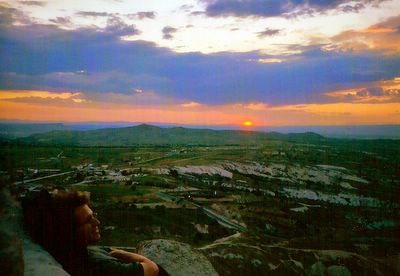

From there, I am transported into a broad valley filled with apricot trees, vineyards, and almost every imaginable flower, all blooming in their spring splendor. On the horizon is a massive snow-capped volcano. Some 10 millions ago,

it erupted and left a warren of lava-shaped canyons and goopy rock formations, which one guidebook compares to the "Grand Canyon on acid." Burrowed inside many of the rocks, a soft, easily sculpted stone made of lava, ash, and mud, are countless caves where locals have lived for thousands of years.

it erupted and left a warren of lava-shaped canyons and goopy rock formations, which one guidebook compares to the "Grand Canyon on acid." Burrowed inside many of the rocks, a soft, easily sculpted stone made of lava, ash, and mud, are countless caves where locals have lived for thousands of years.One of them houses the five-star hotel where I'm staying. Perched on a hill above Cappadocia, the views are only matched by the lavish meals and the attentive staff, with waiters so responsive that a fork set down between bites risks immediate replacement. For such luxury, courtesy of the War on Terror, which has left nearly the entire hotel vacant, I am set back $45 a night.

Following a small stream through one part of the valley, a friend and I arrive in a small, touristy town, where we stop to browse in a carpet shop. Before long, a salesman named Savas is giving us a tour, pouring us apple tea and explaining the differences between cheap wool kilims and silk masterpieces. When he gets the drift we are not the buying kind of customers, he has his driver take us a few miles away to the top of a red canyon, where he leads us on a three-hour hike across mahogany-colored rocks and fields full of irises and poppies. Then, back at his home in the carpet shop, he cooks us dinner, a crispy Turkish pizza prepared in a wood-burning oven.

When I am about to leave this lush

fantasyland - there were moments I considered spending the rest of my life here - Savas suddenly appears at the bus station with a gift, his prayer beads. We hug and I'm on the road again, another all-night bus trip to an unknown city.

fantasyland - there were moments I considered spending the rest of my life here - Savas suddenly appears at the bus station with a gift, his prayer beads. We hug and I'm on the road again, another all-night bus trip to an unknown city.The next morning, I awake to the smell of the sea. The dry air has given way to humidity and with beaches, yachts, and skin-baring sunbathers all around, the place has a much freer feel.

A bumpy ride on a dolmus, or microbus, takes me to the turquoise waters and white-sand peninsula surrounding the legendary Blue Lagoon in Oludeniz. There's a crowd of tourists, but when I glide through the pristine water, which is clear as glass, they seem as far away as the previous night's stressful ride. Then I am on a plateau above the lagoon, beyond several rocky hills covered with pine trees, walking among the ghostly remains of an abandoned town, where thousands of Greeks lived before Turks forced them out when they declared independence from Greek rule in 1923. A few hills beyond is Fethiye, one of the main ports on the Turkish Riviera, and I'm ambling along the crowded harbor, feeling like I'm running a gantlet as scores of aggressive restaurateurs beseech me and every passing tourist to dine with them. Further inland, there is the massive gorge in Saklikent, where a guide escorts me and a group of mostly burly British men through a muddy river that leads to a hidden waterfall.

As I'm feeling the frigid spray of the cascading water, something like a vice closes around my ankle and tugs me a few feet. I wake from my dreams at the bathhouse and stare up at the beefy, shirtless masseuse. If I'm not fully awake, he gets my attention by pouring a bucket of warm water over my head. Then he takes out something like a Brillo pad and begins rubbing off layers of my skin, as if he were trying to remove something sticky from the bottom of a pot. He douses me with more water and begins kneading every muscle in my body, cracking my back, and providing a perverse mix of pain and pleasure. When he is done, after scrubbing me with a bubble bath's worth of suds and washing it away with a combination of hot and cold water, he leaves me alone again.

Still on my back on the warm marble, everything seems more vivid. I watch the beams of light slowly crawl across the cracked floor. I hear the drip-drop of the dozen surrounding fountains, which I like to think once bathed sultans. And then a strange sensation overcomes me, an inexplicable urge for an agnostic unaccustomed to religious feelings.

Perhaps it's primal, but suddenly I feel the desire to hum something holy, a prayer. And then it comes out, from a tune in my mind for anyone listening to hear, some hallowed hymn, which I repeat over and over until I fall asleep again.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe