By David Abel

Globe Staff

12/17/2003

CHIANG MAI, Thailand – To say I’m not a cook would ignore well-honed skills of calibrating a microwave to prepare pre-made dinners and even, on occasion, my dabbling in the art of using a stove to re-heat leftovers.

Not to boast, but I must also acknowledge, after some trial and error, that I’ve managed to master the culinary skill of bringing water to a boil, often for the purposes of preparing pasta, as well as the ability to properly pour milk into my cereal bowl.

So I wouldn’t want anyone to infer I was completely unprepared for my foray into, as the attractive brochure promised, “learning to prepare the fine cuisine of Thailand.”

The first problem was figuring out how to operate the large, sharp knife, without removing one of my fingers. But we’ll come to that.

I decided to take a cooking class here in northern Thailand, the country’s second largest city and what my guidebook called its “cultural heart,” because it seemed a way of eating well for the night – so long as I could partake in the instructor’s creations, and avoid eating my own.

I’m much better at eating than cooking.

The brochure also promised free

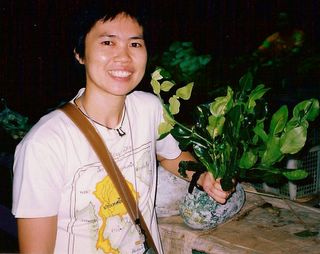

transportation, which came at the appointed hour one afternoon this fall in the form of my 30-year-old teacher, Yui, who met me on a dusty corner of the city in her lime-green Mazda, a car that looked much older than she did.

transportation, which came at the appointed hour one afternoon this fall in the form of my 30-year-old teacher, Yui, who met me on a dusty corner of the city in her lime-green Mazda, a car that looked much older than she did.“Are you ready to cook?” she asked in excellent English.

I smiled and said, “I’m ready to eat.”

We drove through a maze of narrow streets, between the motorized rickshaws and ubiquitous red trucks that serve as local taxis, to her small home on the city’s outskirts. Her husband, children, and other relatives were waiting on the outside patio, the table and frying pans all set up, and I learned, to my delight, I’d be her only student that evening.

I washed up and she presented me a cookbook, with the hope – and this would require a significant reserve of faith – that I’d be able to return home and figure out how to recreate the dishes she would teach me how to make, or at least avoid wrecking.

First up was the staple of any dining experience in Thailand: Pad-Thai. The fried noodles, served often with chicken, pork, or shrimp, are available almost anywhere in this nation of 60 million people, from sidewalk stalls to jungle villages.

I was in luck. I’ve actually made Pad-Thai before, at least the packaged version from Trader Joe’s, which essentially requires little more than my already enumerated skills – boiling water and adding the contents of a sealed package.

This, unfortunately, would require me to tap into a deeper reservoir of talent than I had thus far proven in any kitchen.

In quick order, and making it look as simple as tying her shoes, Yui showed me the eight or so steps, and her secret signature. “Now, it’s your turn,” she said.

But before the good stuff went cold, I had to taste it – to assure myself I would get some return on the 400 baht, or $10, I paid for the class. As good as it looked, it tasted better: One bite of the slivery, oil-covered noodles was enough to know I hadn’t made a mistake.

Following her eyes, I reached for a chunk of tofu on my cutting board and began dicing them in small cubes. I did the same with Chinese chives, which made it readily apparent to Yui that I had no idea what I was doing.

As I chopped away, satisfying myself I was making progress, she watched as I drew perilously close to my fingers on the other side of the large knife. “Stop!” she commanded, and then gently explained, without making me feel like a complete dolt, the proper way of using a knife – that is, holding it close to the blade and keeping at least one finger on the side, for control.

That cleared up, and the shallots and turnips successfully peeled and minced, it was time to fire up the wok and pour in four tablespoons of canola oil. (Sunflower oil works as well, Yui said.) Then, in quick succession, I dropped in the ingredients: The tofu first, and then after it browned, I added the shallots. Twenty seconds or so later, I put in slivers of chicken breast. When they turned white and firm, I added two-and-a-half cups of water and dropped in the dried rice noodles.

I stirred it all around for about 30 seconds and it was time for the secret elements – a tablespoon of fish sauce and soy sauce, a squirt of lime, one and half tablespoons of brown sugar – and the key to the flavor – two tablespoons of tamarind puree.

Then I dropped in two heaps of chives and bean sprouts, mixing them in for about 20 seconds. Next, I cracked open an egg – a skill I’m still working on nearly a decade after college – and, as Yui instructed, let the yolk ooze unevenly, by tilting the wok. The final touch: Two tablespoons or more of roasted, ground peanuts.

Unfortunately, it didn’t look anywhere as tempting as Yui’s. The noodles and eggs seemed overcooked, and I nearly suffered third-degree burns by hovering too closely over the sizzling oil. But when she dropped a small purple flower on top, I smiled. It was mine, after all. And though it may have lacked – OK, definitely lacked – the same flare as Yui’s, it was edible, and for that, I was proud.

With our first meal complete, we hopped on Yui’s scooter and I held on for life as she weaved through a patchwork of potholes and a barrage of old, carbon-spewing cars to get to her neighborhood market.

There, over cement floors that reeked of the refuse sliding through mud-filled gutters,

brightly lit stalls featured every fruit and meat and fish imaginable, some still alive. For an hour, while we sipped coconut smoothies from plastic bags, Yui introduced me to everything from foul-smelling durian fruits to cantaloupe-sized watermelons to oblong eggplants, as well as the frogs and grasshoppers for sale.

brightly lit stalls featured every fruit and meat and fish imaginable, some still alive. For an hour, while we sipped coconut smoothies from plastic bags, Yui introduced me to everything from foul-smelling durian fruits to cantaloupe-sized watermelons to oblong eggplants, as well as the frogs and grasshoppers for sale.Holding up a bag of dried worms, she joked: “Would you like some?”

Afterwards, with the sun now beyond the horizon and a stash of produce in hand, we made the perilous ride home, sans streetlights, or helmets for that matter. The sticky air grew mild and Yui’s assistant had set aside the ingredients for the next two dishes – Gang-Keow Wan-Gai (green curry with chicken) and Tom-Ka Gai (chicken in hot and sour soup, with coconut milk.)

I showed little improvement with the next two meals. But I learned quite a bit, even if I can’t recall much of it anymore, or didn’t quite believe it. Yui, for instance, insisted coconut cream was healthy and lemon grass would be easy to find in just about any supermarket in the States.

Still, after about six hours at her house, not all was lost. For one thing, to say the least, I left without an empty stomach.

Actually, by the end, after consuming some six meals (I ate most of the dishes she prepared) I felt like a mirthful Buddha – proud most of all of my bulging belly.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe