Click here for more photos of Jarabacoa.

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/5/2007

JARABACOA, Dominican Republic – About 25 years ago, after some unfathomable whim led my dad to build a farm in the central highlands of the Dominican Republic, I found myself riding in the back of a rental car, bouncing toward nausea on a narrow dirt road that promised imminent death.

As we climbed into the clouds, looping beside thousand-foot drops and over car-sized ditches, I felt as if I entered some montage of despair in National Geographic. We were as far as I could imagine from our suburban home in New York.

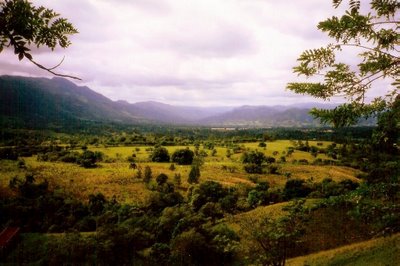

My dad had decided to take the family to see the fruit of his labor in Jarabacoa, an isolated mountain town where pine trees scent the tropical breeze, clear blue rivers carve through velvety green hills, and a rich soil and temperate climate spur the growth of everything from flowers to eggplants to bell peppers – all of which my dad would eventually grow.

Dominicans have long called the town a paradise of eternal spring; to me, my sister, and mom, it seemed more like the gates of hell. As we chugged up the primitive road, passing cliff-side crucifixes and old, smoke-belching trucks that nearly sideswiped us from the opposite direction, I saw a poverty unlike anything I had ever witnessed – zinc-roofed shanties, pregnant women balancing bales of fruit on their head, naked children hawking handmade brooms.

Over the years, sometimes with decades between visits, I've made the same trip, the most recent this past December. In that time, I’ve watched as this sleepy town shed its anonymity, progressed with the shifting direction of the country’s economy, and emerged into a metropolis of about 75,000 people, one that now attracts thousands of tourists a year.

The two-lane road up to Jarabacoa remains a danger zone. There are few if any streetlights, people and animals frequently cross the winding road’s blindspots, and a mix of motorcycles, jalopies, and large trucks race up and down the mountains, often using the oncoming lane of traffic to pass each other.

But the road is now entirely paved, lined by guardrails, and no longer hews to the edge of the cliffs. Zinc-roofed shacks still dot the side of the road, but they’re now mainly built of concrete, not the flimsy wood of decades ago. Children continue hawking brooms, fruit, and the mix of milk and orange juice called morir soñando (to die dreaming), but they’re outnumbered by neon-signed restaurants, freshly painted hardware stores, and the ubiquitous convenience stores called colmados, which sell everything from Presidente beer to the addictive crackers made in the area.

Jarabacoa, a word from the native Taiínos that means “place where the water flees,” lies between the confluence of three rivers that flooded the area when Hurricane David swept the island in 1979, destroying nearly everything in its path, including much of the farm my dad had built only a few months before.

My dad, an accountant who owns a small business selling flowers in Manhattan, had decided to grow his own pompons, daisies, and other bouquet-stock varieties as a check on the volatile prices set by local wholesalers. He began looking for land in Colombia when an employee from Santo Domingo suggested he consider the Dominican Republic. Eventually, he arranged a visit and a government official gave him a tour of possible sites, selling him on the country of 9 million people that borders Haiti on the island of Hispaniola.

With no knowledge of agriculture, at best high school-level Spanish, and hard of hearing, my dad bought about two acres of land beside a mountain and a stream, built four greenhouses, and invested in, among other things, refrigeration equipment, water tanks, and a generator, a vital piece of equipment in a country with constant blackouts.

Over the decades, the farm grew into a larger operation, with additional greenhouses, about 25 acres of land, and scores of employees. In the early 1990s, my dad decided it was time to sell. But things didn’t go as planned. The buyer, who chose to grow bell peppers instead of flowers, ended up defaulting on his payments, and my father had to repossess the farm – as well as learn how to grow peppers.

Since then, the farm has survived a few more hurricanes, devaluations of the peso, even an attempted coup involving a former administrator who held the farm hostage while pressuring my dad to sell it to him for a fraction of its value. (I was drafted to leave my job at a Mexico City newspaper and spend several months here fighting legal battles with the former administrator – who sought to shut the farm down – and learning how to run a pepper farm.)

When I returned in December, I found Jarabacoa had grown as much as the farm, to the point that the town now almost completely surrounds the greenhouses.

As I drove across a rebuilt bridge into the heart of Jarabacoa, passing a new sign welcoming visitors, the air smelled familiar, of smoke from the thick grass burned in the surrounding hills. The slow, melodic pulse of bachata, the country’s aching ballads of love and lost love, seeped from the open-air windows of newly built homes, out of a parked pickup stacked with pineapples, from the radio of old men drinking rum and playing dominoes. All around, palm, lemon, and star-fruit trees swayed in the cool morning breeze.

The road passes an old police station and merges with Avenida de Independencia, one of the town’s potholed main streets, which used to be surrounded by little more than squat homes, spare government offices, and a few stores. Telephone polls remain canvasses for political parties and the rum company Brugal still sponsors most street signs. But now the Avenida is crowded with swarms of scooters, SUVs, and flatbed trucks, some with giant speakers advertising the rapid-fire Spanish and bouncy merengue of local radio stations, no matter what time of day.

Jarabacoa’s central square, once dusty and forlorn save the boys selling shoeshines, now looks manicured, with flowers, plants, and a shiny gazebo. Just off the square, where an enormous, century-old saman (rain) tree shades much of the area, a modern downtown has grown, with Internet cafes, a shopping arcade, supermarkets, a bank, hotel, gym, and restaurants such as the Evolution Bar, Comida Chinaexpress, and Pepperoni Pizza. There's even a small casino.

Many of the changes reflect the nation’s economic growth, which last year amounted to 10 percent. They also reveal the influence of New York, where thousands of locals have lived or have relatives. Then there’s the effect of all the tourists who come to visit the nearby Pico Duarte, the largest mountain in the Caribbean, raft down the pristine, ledge-filled Yaque del Norte, and trek to the town's large waterfalls, Salto Baiguate and Salto Jimenoa.

The road to the farm from the center of town, a previously desolate stretch of dirt where police in powder-blue shirts and white safari hats used to shake us down for bribes, now passes everything from densely built hovels to elegant estates. Uniformed children flood out of newly built schools as European backpackers hike past a mausoleum-filled cemetery to the less-than-inviting Hotel California. From the patios of their small homes, the young and old flash broad smiles to strangers as they gently move back and forth on rocking chairs, a national pastime here as much as baseball.

About a mile from town, a few blocks from the farm, a growing neighborhood – complete with a new pharmacy, elementary school, and convenience store – stretches into Palo Blanco, the lush valley where only open land existed when I first visited. Now, with the town advancing all around, the farm had to erect a fence to keep poachers from raiding the greenhouses.

As I drove past stray dogs picking at heaps of trash, some of it being burned beside the road, I looked up and saw the large green hills shimmering in the distance and watched as a film of dust, kicked up by passing mopeds, created something of a halo over the valley.

When I passed the neighborhood, there it was, pressed even closer that I had remembered it to the town’s urban border.

Rising over the warren of cement, the plastic roofs of the farm’s netted greenhouses magnified the bright sun, releasing a soft perfume from the thousands of carefully tended pepper plants that slowly grow from sprig to more than 6 feet tall. I waved as employees shuttled between jobs looping twine around the plants to keep them upright and filling crates with the end product – large, ripened orange, red, and yellow peppers.

Before greeting the employees, some of whom I have known since I was a child, I stopped to scan the glimmering horizon, suck in the fresh air, and realize how my dad wasn’t as crazy as we all thought he was.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.